Max Wagner, MPP ’24, University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy

In December 2020, the Chicago City Council followed the lead of other blue state jurisdictions by passing zoning reform for accessory dwelling units (ADUs) – secondary housing units that share a single-family lot with a primary residence. Chicago’s Additional Dwelling Unit Ordinance streamlined zoning requirements for basement and attic apartment conversion projects and legalized the construction of backyard coach houses. In some ways, the policy is a return to zoning regulations of the past – it reversed the 1957 ban on new ADUs in five pilot zones dispersed throughout the city. But the program was also designed with a housing affordability lens – it mandates that half of all new units in multi-unit conversions are affordable at the 60 percent area median income (AMI) level for 30 years.

In a press release celebrating the reform, Mayor Lightfoot described the program and specifically praised the affordability requirement, writing, “By increasing affordable housing opportunities for renters, while also helping property owners deal with the financial demands of their buildings, these ADUs will be a major step forward in our ongoing work to support our most vulnerable residents.” Mayor Lightfoot’s hypothesis was that legalizing ADUs would be an effective way to build more affordable housing. Now that the reforms have been in place for nearly three years, it is worth testing the mayor’s hypothesis by evaluating where ADUs have been built and who has benefited. Are ADUs truly providing affordable housing options for the Chicago’s most vulnerable residents?

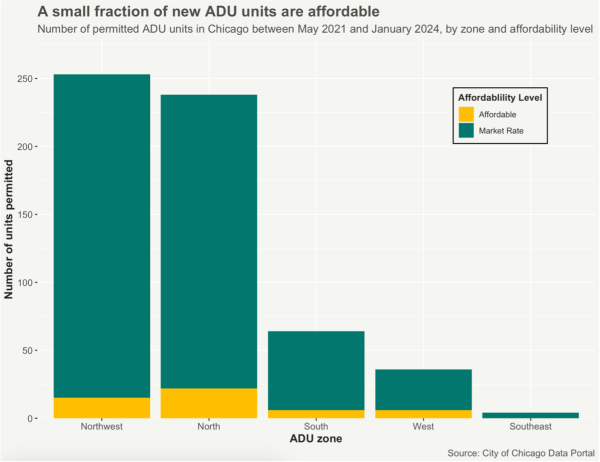

To answer that question, I analyzed the 533 ADU permits issued by the City of Chicago between May 2021 and January 2024. Here are my findings:

- ADU permits are heavily concentrated on the North side of Chicago. 5% of ADU permits are for properties in the North and Northwest zones, which includes large portions of Lakeview, Lincoln Square, Edgewater, Uptown, North Center, Avondale, Logan Square, Wicker Park, Irving Park, Albany Park, Hermosa, and East Garfield Park. The North and Northwest zones also have the highest median rents and median household incomes out of the five zones, per American Community Survey data.

- Only a small fraction of permitted ADU units are affordable. 49 permitted units are legally restricted affordable at the 60% AMI level, out of 595 total units. 37 of those units located in the North and Northwest zones.

The analysis offers reasons to be skeptical of Mayor Lightfoot’s claim that the ADU Ordinance would provide affordable housing to the city’s most vulnerable residents. Most of the new units are being built in zones with relatively high median rents, making it highly questionable whether those units would be “naturally” affordable. A very small number of new units are legally restricted as affordable – especially in comparison to the estimated 120,000 affordable units that are needed in Chicago.

The unique nuances of Chicago’s ADU Ordinance provide one potential explanation for the unequal distribution of ADU permits. The ADU Ordinance sets comparatively strict zoning restrictions for the West, South and Southwest zones. In these areas, only two ADU permits can be issued per block per year. In addition, buildings with one to three units must also be owner-occupied to add a basement/attic unit. Conversely, in the North and Northwest zones, homeowners can build coach houses on vacant lots before a primary residence is built. The stringent rules governing ADUs in West, South and Southwest zones may be preventing some homeowners from applying for ADU permits.

Accessory dwelling unit zoning reform continues to be a popular policy solution for increasing the supply of rental housing. Planners and politicians make grand promises about how streamlined ADU permitting helps solve a whole host of issues from urban sprawl to housing affordability. They argue that ADU reform generates new “naturally” affordable housing units at no cost to the local government. However, more research needs to be done to explore how ADU reforms can be written to truly serve low-income renters.